From the Clintonville Chronicle:

thanks Martin

Jul 15

Posted by Admin in Fire Department History, Historic fire apparatus | 3 Comments

From the Clintonville Chronicle:

thanks Martin

Tags: Chicago Fire Department history, FWD fire truck added to Clintonville's FWD/Seagrave Museum, vintage FWD tractor trailer ladder truck

Jul 13

Posted by Admin in Fire Department History | 1 Comment

This from Dennis McGuire, Jr.:

Engine 108’s old house on Lipps.

Excerpts from bookclubchicago.org:

Lake Effect Brewing Company’s planned move to a historic Jefferson Park firehouse has been scrapped, but the brewer still plans to open a taproom nearby.

Lake Effect Brewing partnered with developer Ambrosia Homes in 2016 with plans to open its first taproom and kitchen on the ground floor of a vacant firehouse at 4841 N. Lipps Ave. Last year, the city council agreed to sell the firehouse, built in 1906, to Ambrosia Homes for $1. Nine rental loft apartments were planned on the floors above. The $2.4 million development was scheduled to be completed by this summer, but the city has been slow to approve needed permits.

The location was approved for a zoning change in 2020 and a liquor sales ban was lifted along the street last year, but with the clock ticking on Lake Effect’s current space at 4727 W. Montrose Ave., the brewery owner said he couldn’t wait any longer. The brewery’s lease is up at the end of the year, and the timeline for the firehouse project remains uncertain. After looking at several empty buildings along the Northwest Side that had the correct zoning and liquor moratorium rules, Lake Effect secured an Avondale storefront this month and plans to move operations in the next few months.

The firehouse development is still moving forward despite delays and is waiting for the city to approve small rendering changes with hopes that construction can begin later this summer. The developer will add a third floor to the firehouse for apartments, which needs to be completed before any work can begin on the ground floor.

If construction can begin later this summer, tenants could move into the apartments by summer 2023.

Tags: Chicago FD Engine 108, Chicago Fire Department history, chicagoareafire.com, Chicagoareafire.com/blog, historic photo of a Chicago FD firehouse in Jefferson Park, Jefferson Park fire station to be redeveloped, Lake Effect Brewing Co, new life for old Chicago firehouse, new use for former Chicago fire house, new use for old Chicago fire station, New use for old Chicago firehouse, new use for old fire house, redevelopment of old Chicago firehouse

May 30

Posted by Admin in Fire Department History | 4 Comments

From Phil Stenholm:

Another installment about the History of the Evanston Fire Department

HAPPY BIRTHDAY!

On May 1, 1975, the Evanston City Council accepted bids for a new 1,000 / 300 triple-combination pumper, with the exact same specifications as the two Howe pumpers purchased a year earlier. The new pumper would replace the 1952 Pirsch 1000 / 100 TCP (Engine 25) that was originally Squad 21 before being rebuilt as a TCP by General Body in 1966. Mack came in with the low bid of $53,725, beating out FWD Seagrave, Pirsch, and several other apparatus manufacturers for the contract. As expected, EFD Chief George Beattie specified that the new Mack pumper be painted “safety yellow,” just like the two Howe pumpers delivered in 1974 and 1975.

In addition, Chief Beattie received a new Plymouth sedan (fleet # 301) in 1975 that was painted red instead of “safety yellow,” with the chief’s 1973 Plymouth station wagon transferred to the platoon commanders as the new F-2 after a light bar was installed on the roof replacing the portable “Kojak light.” The former F-2 (1971 Dodge station wagon) was transferred to the Fire Prevention Bureau (FPB) to be used by the newly-created fire investigation unit (“arson squad”) that would be staffed each shift by a trained fire investigator. Firefighters Bob Schwarz, Pat Lynn, and Jim Hayes were appointed fire investigators by Chief Beattie. As part of the reorganization, one of the two FPB captain positions was eliminated after Capt. Joe Thill retired.

Also, as part of the contract resulting from the firefighters strike of February 1974, the average work-week for firefighters was reduced from 56 hours to 54 hours, with two new positions created in the EFD in 1975 that increased total membership from 100 to 102. One fireman would now be assigned each shift to cover for a fireman absent while on a “short day” (formerly known as a “Kelly Day”), with three firemen on each shift covering for vacations and sick leave. As a result, the de facto EFD minimum shift staffing was reduced from 28 to 27, with six three-man companies (the five engine companies plus Truck 22), two four-man companies (Truck 21 and Squad 21), and the shift commander (F-2).

Eighteen new firefighters were hired in 1974-75, including Samuel Boddie, Art Miller, Bill Betke, Jim Potts, Dave Lopina, Bob Hayden, Mike Adam, Don Gschwind, Thomas Simpson, Joe Hayes, Bob Wagner, Keith Filipowski, Ken Dohm, Tom Kavanagh, Milton Dunbar, Ward Cook, Jim Keaty, and Donald Williams. Also, Fireman James “Guv” Whalen was promoted to captain, firemen Harry Harloff and Ken Perysian retired after 23 years of service, and several other firefighters resigned.

On Wednesday, May 28, 1975, the Evanston Fire Department responded to a report of a fire in the rear storage yard of the Rust-Oleum Corporation at 2301 Oakton Street. A second alarm was struck immediately upon arrival of the first companies, and a MABAS box was eventually pulled, the first time the EFD had requested a MABAS box since the system was implemented in 1968.

At the peak of the fire, 19 2-1/2-inch hand lines, two deluge nozzles, one multi-versal, one ladder pipe from Truck 22, one street jack, and one deck gun from Squad 21 supplied streams that were played onto the storage yard and nearby exposures, as numerous 55-gallon drums full of paint exploded and were sent hundreds of feet into the air. Evanston police temporarily evacuated some of the residences to the east and north.

A 200,000-gallon water storage tank located at the southwest corner of Cleveland & Hartrey was supplied by a 24-inch feeder main that extended south from Church Street. The storage tank fed a 1,000-GPM pump owned by Rust-Oleum and operated by their company fire brigade, as well as the standard ten-inch and twelve-inch residential mains in the neighborhood. Engines from the Evanston, Skokie, Wilmette, Morton Grove, and Winnetka fire departments pumped water from numerous hydrants located to the east and north of the fire, including one hydrant at the dead-end of Cleveland Street at the C&NW RR Mayfair Division tracks 1/4 mile north of Rust-Oleum.

The conflagration was eventually surrounded, drowned, contained, and extinguished, but not before causing $775,000 in damage, making it the fourth highest loss from a fire in Evanston’s history up until that point in time. Only the fires at the American Hospital Supply Corporation (October 1963), the Rolled Steel Corporation (January 1970), and Bramson’s clothing store (October 1971) cause greater damage. If nothing else, the Rust-Oleum fire was certainly the most spectacular fire in Evanston’s history!

The next day — May 29, 1975 — the Evanston Fire Department celebrated its centennial. Although May 29, 1875, was the date that the EFD was legally established by ordinance, the actual genesis of the village fire department was January 7, 1873, when the 60-man volunteer Pioneer Fire Company of Evanston was accepted for service by the village board.

The purpose of the fire department ordinance of May 29, 1875 was not to create a firefighting force. The Pioneer Fire Company — renamed “Pioneer Hose Co. No. 1” in December 1874 when the Holly High-Pressure Waterworks was placed into service — already existed, and had existed for more than two years. Rather, the real purpose of the ordinance was to legally describe the method by which additional volunteer fire companies could be organized and accepted for service with the village going forward, since by May 1875 the C. J. Gilbert Hose Company was already in the process of being organized, chartered, and trained.

Once the C. J. Gilbert Hose Company was ready to be accepted for service, the ordinance needed to describe the relationship between the two hose companies. They might be rivals, but they could not be competitors. They had to work together for a common purpose. Also, the ordinance legally installed the fire marshal as chief of the fire department, with the two hose companies plus any other companies that might eventually be organized and accepted for service officially and legally under the command and direction of the fire marshal.

Tags: C. J. GILBERT HOSE COMPANY, Chicago Fire Department history, chicagoareafire.com, Chicagoareafire.com/blog, Evanston FD Chief George Beattie, Evanston Fire Department history, History of Evanston Fire Department, Phil Stenholm, Pioneer Fire Company of Evanston, Pioneer Hose Co. No. 1, Rust-Oleum Corporation fire in 1975

May 16

Posted by Admin in Fire Department History | 2 Comments

From Phil Stenholm:

Another installment about History of Evanston Fire Department

The concept of the “paramedic” in a non-military, civilian environment, was introduced on a limited basis in several American cities in the late 1960’s, mainly to improve life-saving care to cardiac patients. In 1972, the NBC-TV series Emergency! provided the American public with a weekly glimpse into the world of Los Angeles County Fire Department paramedics, helping to spread the idea across the nation. What was unique about the Los Angeles County Fire Department’s paramedic program was that firefighters were cross-trained as paramedics.

In the Chicago area, fire departments with a tradition of providing ambulance service were the first to train paramedics and place Advanced Life Support (ALS) Mobile Intensive Care Unit (MICU) ambulances into service. The Niles Fire Department – which had provided ambulance service to its residents since 1946 – established a paramedic-program in 1973. The Skokie Fire Department placed two MICU ambulances staffed with paramedic firefighters into service in 1975, replacing its two 1969 Cadillac Basic Life Support (BLS) ambulances.

The Chicago Fire Department, which had provided ambulance service since 1928 and had 33 Cadillac and Pontiac BLS ambulances in service in 1974, placed their first two paramedic-staffed MICU ambulances into service in July 1974, with Ambulance 41 replacing Ambulance 1 at E1/T1 and Ambulance 42 replacing Ambulance 21 at E13. Five additional CFD MICU ambulances were in service by the end of 1974, with Ambulance 43 replacing Ambulance 11 at E22, Ambulance 44 replacing Ambulance 24 at E57, Ambulance 45 replacing Ambulance 2 at E103, Ambulance 47 replacing Ambulance 7 at E108/T23, and Ambulance 16 at O’Hare Field.

The City of Evanston borrowed an MICU “demonstrator” – minus the drugs and the specialized ALS gear only paramedics would be certified to use – from the State of Illinois Department of Public Health in June 1974, and it was tested over a 60-day period by the EFD. It was a modular ambulance, meaning it was a cab & chassis with a “box” mounted on top of the chassis. Personnel from Squad 21 were assigned to the unit (known as Ambulance 1) and responded to inhalator calls and ambulances runs city-wide throughout the summer. An engine company was dispatched as a “first responder” for inhalator calls outside Station # 1’s first-due area.

photographer unknown

Tags: Chicago Fire Department history, chicagoareafire.com, Chicagoareafire.com/blog, Evanston Fire Department history, Evanston Police Chief William McHugh, History of Evanston Fire Department, Los Angeles County Fire Department paramedics, NBC-TV series Emergency!, Niles Fire Department, Phil Stenholm, Skokie Fire Department

Mar 2

Posted by Admin in Fire Department History, Reader submission | 5 Comments

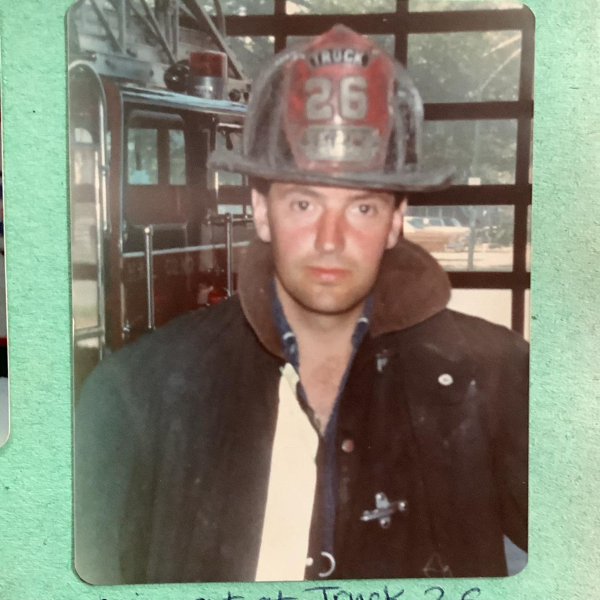

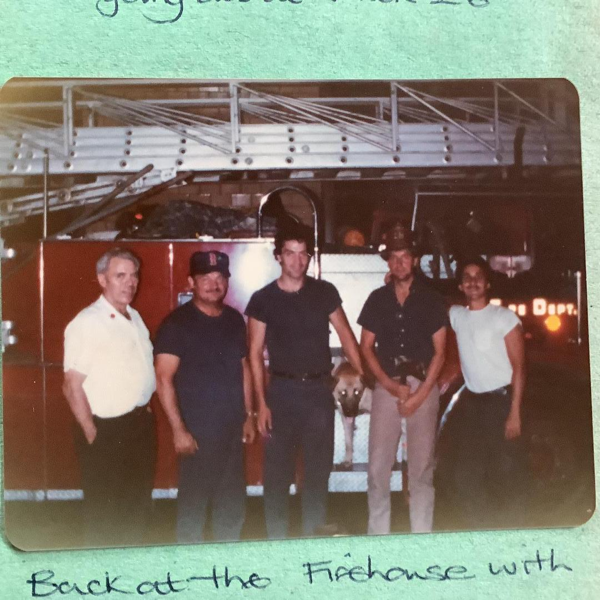

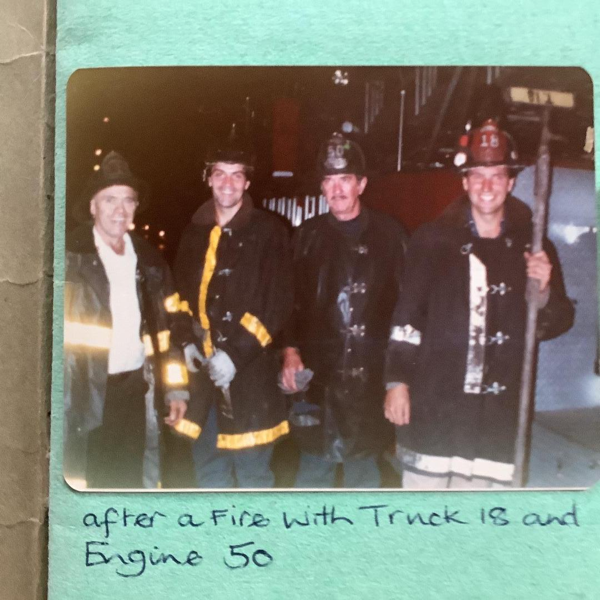

This from Danny Richardson:

Hello does anyone know these Chicago Firefighters from 1982? I was at Engine 50 truck 18 visiting from London (ex London Fire Brigade) and spent some time at what they called the Snake Pit! going on calls . If you can help or put me in touch with anyone that can I would appreciate it.

Kind Regards Danny Richardson

The young buck in the pic is me. Good memories.

Tags: Chicago FD Commissioner William Blair, Chicago Fire Department history, vintage Chicago Fire Department firefighters

Mar 2

Posted by Admin in Fire Department History, Historic fire apparatus | 10 Comments

This from Drew Smith:

In these photos of the old CFD squad, does someone know what the device on the left side of the tailboard is used for?

Tags: Chicago Fire Department history, vintage Chicago FD Autocar Squad 1, vintage Chicago FD squad

Excerpts from the southern.com:

The year after the Great Chicago Fire, city officials kept their fingers crossed and hired six Black firefighters.

The Tribune reported on Dec. 6, 1872, that a Black fire company would be stationed on the foot of May Street, and cautioned those who might decide to protest: “Any infringement on the rights of the members by the people residing in the vicinity will be punished by the removal of the engine.”

That was a credible threat in a city where 300 had been killed and 100,000 made homeless by the enormous fire of 1871, for which the city’s fireD department was woefully unprepared. New pumpers were acquired, including one to be staffed by the city’s first Black firemen.

Even if city officials hadn’t foreseen that a small measure of integration would be anathema to white Chicagoans, they would have realized that the day after Engine 21 with its Black crew was assigned to May Street, near the site of the previous year’s fire.

Two crew members ordered drinks at Chaplin and Gore’s saloon on Monroe Street, as the Tribune reported. They were told Black people weren’t served at the bar. “One of them appeared to take the refusal in good part, but the other fellow declared it was a direct insult to the whole fire department, of which he was proud to be a member.”

Mr. Gore won the physical confrontation that followed but said he would complain to the fire marshal about his missing gold watch.

Engine 21?s firemen were not about to acquiesce to the indignity they’d experienced in Southern childhoods.

Born a slave in Kentucky, Stephen Paine served in the Union Army, then came to Chicago where he worked as a coachman. Being a fireman gave him a social standing equal to white people. Others on Engine 21?s crew had taken a similarly big step up. When challenged, they were more likely to fight back with a demonstration of their prowess than their fists.

In 1885, Engine 21 was called to the scene of a lumber fire that threatened the South Side and the adjoining town of Lake.

The crowd of spectators made fun of the men as they dragged their hose in, according to a Tribune report. “But the levity was soon succeeded by admiration. … They went up to within 10 feet of the burning lumber pile so full of danger to the city and Lake, and soon made an impression on the flames. The pipe got away from three of them once, but the fourth held on though he was knocked down and thrown around and knocked around on the ground.”

Still, why did city officials risk confrontations between Black firemen and racist whites, given all else they had to do to get Chicago up and running in 1872? The credit is due to Mayor Joseph Medill, says Dekalb Walcott, Jr, author of “Black Heroes of Fire,” an account of Engine 21.A retired battalion chief, Walcott notes that Medill was committed to the cause of Black people’s freedom.

As editor of the Chicago Tribune he championed Abraham Lincoln for president and hectored him to issue the Emancipation Proclamation. Elected mayor after the Chicago Fire, Medill rejected his own Republican Party’s courting of voters grown weary of the race issue.

Indeed, Engine 21 would experience mixed fortunes as the nation swung to the right in the 1870?s. Its initial captain was white, and in 1889, the city turned down a petition for Engine 21 to get its first Black captain. That was hardly surprising. From the beginning, its Black crew was badmouthed.

In 1874, F. A. Bragg, a real estate dealer and former volunteer fireman, told insurance adjusters evaluating Chicago’s Fire Department that Engine Co. 21 was political payback to the Black community.

He thought the men “were good drivers and horsemen, generally, but not good firemen,” the Tribune reported. “There was no lack of good and experienced firemen in the city and the existence of this company kept just so many efficient men out of the force,” Bragg insisted. In response to that put-down, Black firemen strove to prove themselves as good, if not better than, white firemen.

In the 1870s, pumpers were drawn by horses stabled on a fire station’s lower floor. The firemen lived on the upper floor and were graded on how fast they could get downstairs and the engine out the door. Seconds matter to someone trapped in a building on fire. Not only did Engine 21 consistently get excellent reviews, but it added a tool to a fireman’s kit that quickened the response time of all companies. A Tribune reporter was shown the prototype by Paine, the former slave, on a visit to Engine 21?s quarters in 1888. “Steve brought it out,” the reporter noted. “It was polished a dark brown and was smooth as ebony and was handled by Steve something as an old battle-flag is handled by a soldier.” It was a pole used to hoist hay to the third floor, where feed for the horses was stored. One day an alarm was sounded, and George Reed slid down the pole and was waiting for the other firemen, who took the stairs.

That prompted David Kenyon, the company’s white commander, to ask his superiors if a circular hole could be cut in the second floor and the pole installed permanently. Walcott notes that permission was granted on condition that if the experiment failed, he would pay for repairing the floor. It worked, and the fire department’s annual report for 1878 noted that sliding poles were being installed in firehouses across the city. The later ones were made of brass, as sliding down a wooden one meant a fireman sometimes took a sliver with him.

For Kenyon, the invention kick-started his rise through the department’s ranks. As deputy fire marshal, he was thrown from his buggy, run over by an engine, and died of his injuries in 1887.

Though the sliding pole was adopted worldwide, it didn’t end the harassment of Engine 21?s crew or quicken the department’s integration. To the contrary, when a Black fireman was assigned to Truck 17, the white firemen burned a Black man in effigy, the Tribune reported in 1907, writing that the white members were so against the idea of a Black colleague that the firemen said they wouldn’t sleep in the same dormitory with him.

The first Back captain was appointed in 1923, and a second Black company was established in 1943. With each small breakthrough, more Black children experienced a thrill a Tribune reporter witnessed when Engine 21 went roaring out of its quarters in 1888.

Little by little, the Black community’s demand for an equal shot at fire fepartment positions grew more insistent. In 2011, a judge ordered the city to hire 111 Black firefighters as compensation for its discriminatory practices. Female applicants won a similar lawsuit.

And so it was that in 2021, a mere 143 years after a Black fireman slid down the first fire pole, Annette Nance-Holt, a Black woman, was appointed commissioner of the Chicago Fire Department.

Tags: Black history month, Chicago Fire Department history, Chicago Mayor Joseph Medill, history if Black firefighters in Chicago, the first black firefighters in Chicago

Dec 30

Posted by Admin in Fire Department History, Historic Fire Photo | Comments off

From Steve Redick:

February 12, 1971 4-11 at 15th & Karlov

photographer unknown

Tags: Chicago Fire Department history, historic fire scene photos, Vintage 4-11 Alarm fire in Chicago 2-12-71, vintage fire scene in Chicago

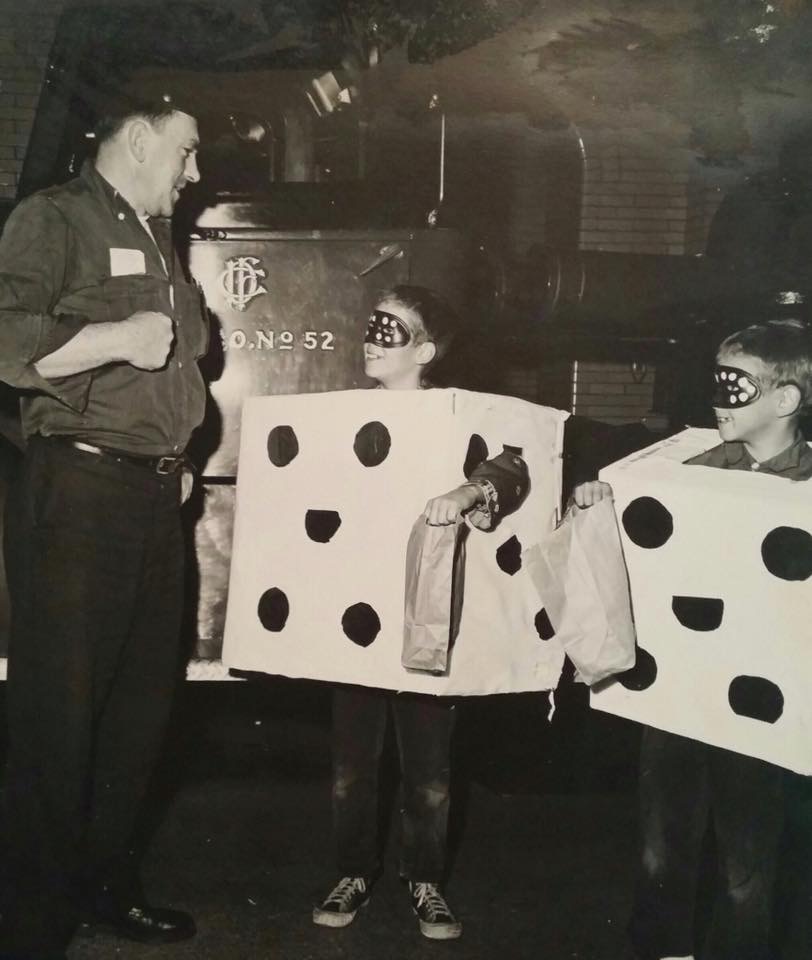

This from Michael Christensen:

Historic photo Halloween 1961 Truck52 Engine 65

Historic photo Halloween 1961 – Chicago FD Truck 52 Engine 65

Tags: Chicago Fire Department history, video of vintage Chicago fire apparatus

Oct 23

Posted by Admin in Fire Department History, Fire Scene photos, Historic Fire Photo | Comments off

From Steve Redick:

July 1970, location unknown

photographer unknown

photographer unknown

photographer unknown

Tags: Chicago Fire Department history, vintage photo of Chicago Firefighters battling a fire in 1970

For the finest department portraits and composites contact Tim Olk or Larry Shapiro.

Arclite theme by digitalnature | powered by WordPress