Excerpts from the DailyHerald.com:

Pingree Grove & Countryside Fire Protection District Chief Mitch Crocetti receives $117,500 a year in his current role, but his pension after his previous 30-year career with the Wood Dale Fire Department also pays him $124,037 annually.

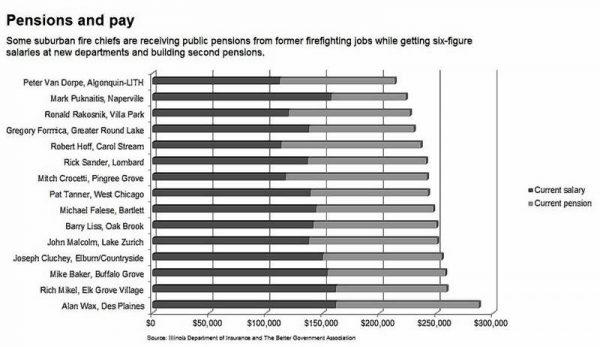

Crocetti is one of at least 15 suburban fire chiefs who are drawing six-figure salaries while receiving pensions and building toward eventual second public pensions, according to a Daily Herald analysis of fire pension records.

He said smaller fire departments benefit by being able to pay lower salaries to retirees on pensions. “That’s how a lot of these smaller departments can afford to have experienced, educated chiefs,” Crocetti said. “Without these kinds of benefits, I don’t know how a smaller community could draw someone.”

However, Naperville Republican state Rep. Grant Wehrli wants to end the perk. He plans to introduce a bill next session that will mirror the legislation he successfully championed last year for police. When that law becomes effective Jan. 1, police retirees who are collecting pensions can’t take new police jobs and be eligible for second pensions.

“It’s an egregious abuse of the pension systems that allows someone to collect a retirement benefit while still working in the same line of work,” Wehrli said.The 15 chiefs average an annual salary of $137,597 while also receiving pension payouts that average $104,762.

Carol Stream Fire Protection District Chief Robert Hoff makes more from his Chicago Fire Department pension — $122,472 — than he does from his current salary of $113,645. All the others receive more from their current salary than from their pensions.

With his $161,709 salary and $125,624 pension from the Highland Park Fire Department, a total of $287,333, Des Plaines Fire Chief Alan Wax receives the highest combined annual payout of the 15 chiefs. Next year, his 10th with Des Plaines, he becomes vested in his new pension program.

“It’s triple dipping,” argued Madeleine Doubek, vice president of policy at the Chicago-based Better Government Association. “I think most of us believe a pension is supposed to be something that you collect when you’re no longer working a full-time job, and that’s clearly not what’s happening here.”

In Warrenville, Dennis Rogers Jr. is paid to be fire chief while also receiving an Illinois Municipal Retirement Fund pension as a former sheriff’s deputy. He also participates in the Warrenville Fire District’s pension plan and eventually will be eligible to receive that second pension.

Several more fire chiefs are collecting pensions from their former fire departments or districts but opted for different retirement benefits at their new departments. Some received as much as 15 percent of their annual salaries paid into 401(k)-like retirement programs designed for public employees.

Firefighters contribute about 9.5 percent of their pay toward their eventual pensions. Most fire pension funds expect a 7 percent return on investment income each year. The strength of the fund’s investment returns determines how much money taxpayers owe the fund each year. If the investment target isn’t reached, taxpayers have to pay more.

However, most towns or fire districts haven’t fully funded pensions for years, so most taxpayers these days wind up paying more each year to make up for previous years’ shortfalls.Crocetti complained that funding shortfalls from the past are the main reason public pensions have come under attack. “I don’t get the right to say I’m going to contribute less than what I’m supposed to and I’ll catch up in a couple years,” he argued. “That’s what started this mess, and now we’ve lost out on all that investment income that we’ll never get back.”

Firefighters get 75 percent of their final salary as a starting pension after 30 years of work. They can begin collecting at age 50. The pension grows 3 percent each year.

Most other public employees can’t have multiple pensions because jobs like teachers, librarians, judges, legislators, city workers, and university professors are all handled under statewide retirement systems. That means a librarian can’t retire from one town after 30 years and start collecting a pension, then go work at a library in a neighboring town and start the pension contribution process all over again. Most other public workers have to put in more than 40 years on the job to maximize their retirement benefits as well.

Meanwhile, there are more than 600 separate and autonomous police and fire pension boards in the state, and that’s the main reason firefighters and police have been allowed to collect pensions and start new ones at different departments.

“There are all kinds of groups out there that recognize the inefficiency of 600 different pension funds,” Doubek said. “There are clearly more efficient ways to do this and not perpetuate the situation, and the legislation for the police ought to be a model for all public employees.”

Wehrli’s bill ends that pension loophole for police in a few weeks. While police won’t be able to start contributing to a new pension from another department or municipality in most cases, theoretically they could get a job with a state agency, as a teacher or even as a legislator and start building a new pension.

thanks Martin