The Chicago Tribune has an article about former Chicago Fire Commissioner Robert J. Quinn:

On Oct. 18, 1958, a bizarre-looking apparatus responded to a blaze at a lumberyard on Cermak Road, raised a steel arm hinged in the middle like an elbow, and revolutionized firefighting the world over.

“A fireman in a crow’s nest at the top of the tower directs the stream and gets his orders from below by observers using a walkie-talkie radio,” the Tribune reported.

Shortly, the new firetruck was lettered “Quinn’s Snorkel,” and with good reason. Fire Commissioner Robert Quinn’s brainchild enabled firefighters to stand firmly on a flat platform instead of precariously clinging to the top rungs of a ladder. Shortly after becoming commissioner in 1957, Quinn saw tree trimmers using an aerial platform and realized its potential for attacking fires. Other fire departments quickly followed Quinn’s lead.

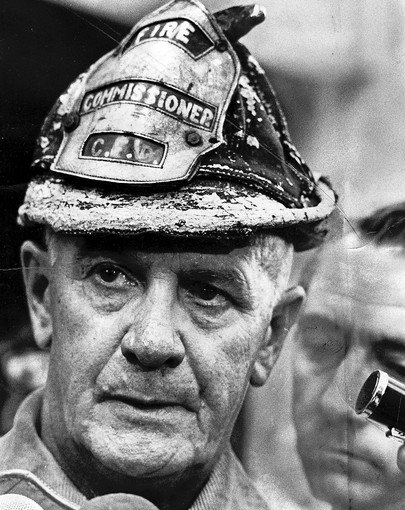

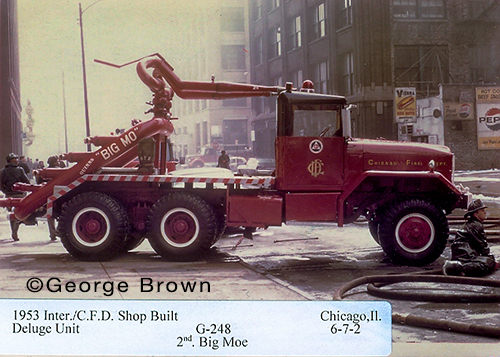

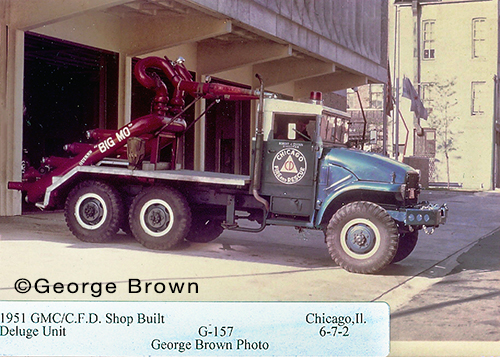

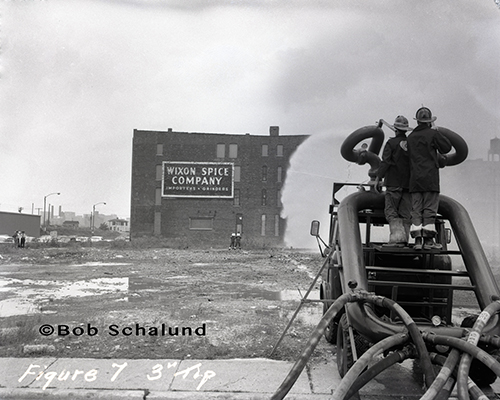

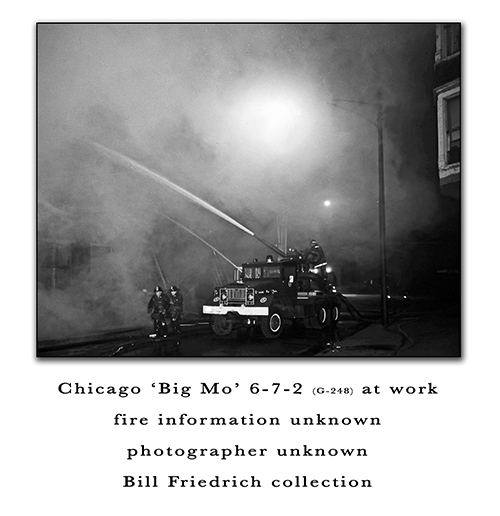

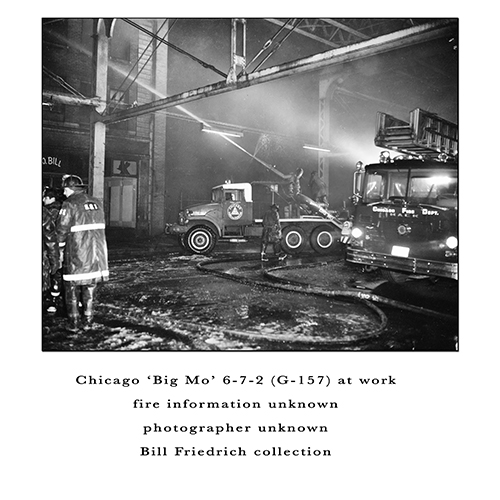

In his 21 years as commissioner, the colorful and innovative Quinn was always good newspaper copy. He responded to fires wearing a battered old helmet. He equipped fire vehicles with radios, constructed humongous water cannons with fanciful nicknames like “Big Mo,” acquired helicopters that gave fire chiefs a bird’s-eye view of a blaze and established a photographic unit so fires could be documented and studied.

Fire Commissioner Robert Quinn regularly responded to fires wearing a battered old helmet. (Chicago Tribune file photo)

He was named commissioner by Mayor Richard J. Daley — the two were alums of Bridgeport’s Hamburg Athletic Club, a neighborhood hangout — though Quinn denied street corner loyalties got him the job. “We lived west of Halsted Street, and he (Daley) lived east,” Quinn told a Trib reporter, “and that made a difference in those days. You never had anything to do with the guys on the other side of the tracks.”

Either way, Quinn’s reign over the Chicago Fire Department corresponded with Daley’s reign over the city. He was eased out by Daley’s successor Michael Bilandic in 1978, though he wanted to serve another few months, making him a firefighter for half a century.

Quinn presided over major fires — including the horrific Our Lady of the Angels school fire in 1958, the one that destroyed the original McCormick Place in 1967 and the 1968 West Side riot conflagration — during years when fire deaths were all too common: 206 in 1963 (the worst in modern times), compared with 16 in 2013 (the lowest).

He also kept Chicagoans alternately amused and bemused with madcap antics and the tall tales with which he explained them. As a Tribune editorial noted when Quinn stepped down, he had provided “us all with a few special stories to tell friends from out of town.”

In 1969, a 19-year-old Irish immigrant was overcome by smoke in a Lake Shore Drive apartment rented by Quinn. He explained his presence at the scene by saying he went there from the Marina Towers apartment where he lived to direct firefighting operations. “I hadn’t been in the apartment for two years until last night,” Quinn said. He explained that he met her in Ireland while searching for his parents’ birthplace and helped her come to America. In some versions of the story, she was a distant relative; in others, the friend of a friend.

When it was disclosed that a fire lieutenant was detailed to Quinn’s Wisconsin farm, he explained the officer was a good match for the assignment. “He’s really good with animals,” Quinn said.

When the White Sox clinched the American League pennant with a late-night victory in September 1959, Quinn set off the city’s air-raid sirens. At the height of the Cold War, some Chicagoans thought it signaled not a forthcoming World Series but an atomic Armageddon. “If the Sox ever win another pennant, I’ll do it again,” Quinn said.

Yet for all his goofiness, Quinn was a hero. In 1934, he climbed eight stories to rescue three civilians from a fire in a Loop building. The same year, he put a 200-pound woman over his shoulder and, with her clothing on fire, leaped 4 feet to an adjoining building. For that feat, he was awarded $100 as the Tribune’s hero of the month.

Serving in the Navy in World War II, Quinn was decorated for heroism during a three-day battle against a fire on a tanker loaded with aviation fuel.

He returned to Chicago convinced that a fire department should be run like a military organization. More than a bit of a martinet, he tried to introduce naval-style dress uniforms that his firefighters decried as “sailor suits.” A national champion handball player, Quinn subjected recruits to the physical-fitness regimen he followed. To publicize it, he sponsored a marathon run for firefighters from Chicago to what is now Naval Station Great Lakes that caused a massive traffic jam on the highway that he appropriated for the event.

A 1969 study faulted Quinn’s department for being slow to equip firefighters with the breathing apparatus that can make the difference between life and death. Quinn said the department couldn’t afford them.

He famously opposed switching from limousine ambulances to the boxy, modern vehicles, “apparently on the theory that a Chicagoan would rather die in style than be saved in the back of a panel truck,” the Tribune noted.

Quinn thought firefighters should be “he-men.” He told a reporter he was disgusted by pictures of firefighters with long hair in fire-industry publications. “If the good Lord wanted a man to look like a woman, he would’ve made him a woman,” he said. His racial views were equally antediluvian. He answered critics who said his department discriminated against African-American firefighter applicants by saying blacks “don’t like heat and smoke.”

In the years since, whole doses of Quinn’s approach to firefighting have been abandoned. Although Chicago still runs his beloved snorkels, other cities have scrapped them in favor of telescoping ladders with aerial platforms.

A bit of advice he gave to recruits 40 years ago is still worth pondering. A firefighter, he noted, must be ready to go instantly from sitting around the station to hopping on a rig, prepared to put his own life at risk to save another’s.

“When you get out in the field, you’ll be sitting on your ass for a long time,” he said. ” Be ready to go to work. Pay attention to the rules. Compete in sports. Stay in shape. Get your hair cut. And for Christ’s sake, be men.”

thanks Scott, Drew & Dan