From Rob:

Found on Facebook

Found on Facebook

From Rob:

Found on Facebook

Found on Facebook

Tags: #FAJ, Chicago Fire Department history, chicagoareafire.com, Fire Apparatus Journal

Feb 28

Posted by Admin in Fire Department History, FIre Stations | Comments off

This from Dennis McGuire, Jr:

The rehabilitation of two historical Jefferson Park buildings could help revitalize the neighborhood, and the developer is looking for tenants.

For the past eight years, developer Tim Pomaville has been working to transform the Jefferson Park firehouse at 4841 N. Lipps Ave. into a mixed-use residential development. The initial plans involved Lake Effect Brewing Company setting up its taproom on the ground floor, but years of delays and complications to buy and rezone the property prompted the brewery to pull the plug in 2022.

Ambrosia Homes, Inc. has similar plans for the Lero building at 4762 N. Milwaukee Ave. Pomaville. Both buildings are ready for commercial tenants to draw people to Jefferson Park. Ambrosia Homes unveiled plans to invest $2.4 million into the former Jefferson Park firehouse in 2018.

Built in 1906, the firehouse has been vacant for years. The city council agreed to sell the property to Ambrosia Homes in 2021 as part of its $1 land sale program. Ambrosia paid $208,000 to the city, which used the money for remediation reimbursement. Lead paint and asbestos had to be removed from the fire station.

With Lake Effect’s taproom on the ground floor, the plan was to add a third floor and building nine apartment units in the upper levels.

The property had to undergo a zoning change in 2020, and a liquor sales ban was lifted along the street in 2021. After six years of waiting, Lake Effect couldn’t weather any more delays as its lease at 4727 W. Montrose Ave. was up at the end of 2022, the owner said at the time. Instead, the brewery found a different location.

Now, Ambrosia Homes is looking for another business to take over the space. The ground floor could be split into two 4,000-square-foot units that would each be rented for about $3,700 a month. Plans for the residential portion of the building have also changed. The firehouse will likely remain two stories, and the upstairs will have four apartments.

While some potential tenants have asked about buying the firehouse, Ambrosia Homes is not looking to sell.

Named after its former owner, the building functioned as a billiard hall and amateur boxing ring in the 1920s. Over the years, the two-story bow truss building has also housed a relief center for people struggling with food insecurity, a community hall and a furniture business. The building has largely sat vacant for the past 30 years.

The Lero is a prime location just a short walk from the Jefferson Park Blue Line station and next to a cannabis dispensary called Cannabist, which revitalized two empty storefronts in 2022.

Like the Jefferson Park firehouse, the Lero’s ground floor could be split into two 5,000-square-foot units. Rent for each would be $3,800 a month, but Ambrosia Homes is willing to sell the building for $695,000.

If Ambrosia retains ownership of the Lero, they plan on building six apartments on the upper floor and are considering adding a third floor. The building has six parking spots in the back.

Tags: Chicago FD Engine 108, Chicago Fire Department history, chicagoareafire.com, Chicagoareafire.com/blog, Jefferson Park fire station to be redeveloped, Lake Effect Brewing Company, new life for old Chicago firehouse, new use for former Chicago fire house, new use for old Chicago fire station, New use for old Chicago firehouse, new use for old fire house, redevelopment of old Chicago firehouse

Jan 19

Posted by Admin in Fire Department History, Fire Truck photos, Historic fire apparatus | 13 Comments

This from Andrew McCullough:

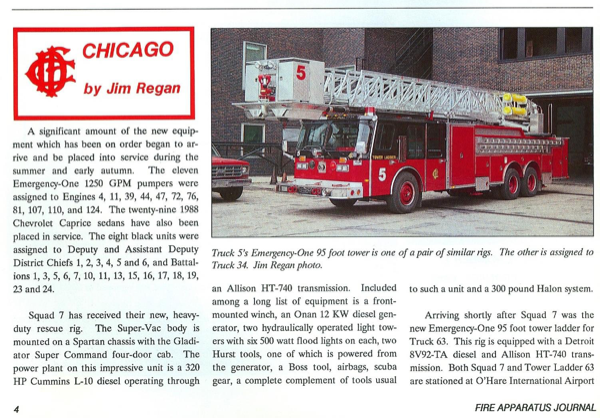

Here are a few more of my dad’s old slides. The descriptions on the slide tray are:2-3: Truck 312-5: Squad 2’s rig at E5’s house (not sure why the rig says 6, taken in 1966)2-6: Salvage #1 (281) at E5’s house (taken in 1966. The Autocar squad is behind, and the gas truck is barely showing on the left of the frame)2-8: My first rig as engineer on E5 – 1952 FWD (taken in 1966 in front of E5’s house).2-31: Still alarm 700 W Jackson2-32: Still alarm 700 W Jackson2-33: Still alarm 700 W Jackson2-35: Still alarm 700 W Jackson

Andrew McCullough collection

Andrew McCullough collection

Andrew McCullough collection

Andrew McCullough collection

Andrew McCullough collection

Andrew McCullough collection

Andrew McCullough collection

Andrew McCullough collection

Tags: 1952 FWD ladder truck in Chicago, Andrew McCullough, Chicago FD Autocar squad, Chicago FD Salvage Squad, Chicago Fire Department history, chicagoareafire.com, classic Chicago FD B-Model fire engine, historic Chicago FD photos, John McCullough

Jan 4

Posted by Admin in Fire Department History, Fire Truck photos, Historic fire apparatus | 3 Comments

This from Andrew McCullough:

This is a scan of one of my father’s slides. He was engineer on E5 at the time. The engine is a 1969 Seagrave 1500 GPM. It was close to new here, so this must be 1969-70.Location is E5’s quarters 324 S Desplaines St. Photo by the late John McCullough.

John McCullough photo

Tags: 1969 Seagrave fire engine, Andrew McCullough, Chicago FD Engine 5, Chicago Fire Department history, chicagoareafire.com, Chicagoareafire.com/blog, classic fire truck, John McCullough, vintage Seagrave fire engine

Dec 28

Posted by Admin in Fatal fire, Fire Department History | 5 Comments

From the National Fallen Firefighter’s Foundation:

On a cold Chicago morning, shortly after 2:30 am on December 17, 1953, Chicago firefighters received a report of fire at the Reliance Hotel at 1702 West Madison Street. Firefighters arrived at the scene promptly, only to find the three-story hotel in flames. The fire quickly escalated to three alarms, bringing 100 firefighters to the scene.

At the time, the skid row hotel was being remodeled—but was still open for business. The hotel manager awoke to a smell of smoke and alerted the guests on his way to the first floor to report the fire; a police patrol also reported the fire at around the same time. Seventy-five occupants were rescued; all but one of its occupants escaped unharmed: a 45-year-old resident, who is believed to have set the fire. Officials found a note in his pocket confessing to several crimes in addition to setting fires in 12 apartment buildings.

Firefighters were working feverishly to contain the fire when, without warning, the front of the building collapsed at around 3:49 am. Those on the roof rode on top of the collapsing building and were able to rescue themselves after the fall. One firefighter described it as “like sliding down a chute.” Fire crews working inside the building weren’t as lucky, and dozens were missing following the collapse.

Ice-encrusted firefighters worked for six hours, digging through the debris with their hands and tools while others continued working to contain the fire. The blaze was contained after 4:30 am.

After the fire was under control, crews continued to work to rescue the trapped and injured firefighters. They worked in frigid temperatures to free their colleagues, under the risk of a secondary collapse. The Chicago Daily News reported that “At the height of the rescue work, all of the city’s police and fire resuscitators were at the wreckage to revive firemen as they were rescued.” The Salvation Army and Red Cross provided food, hot beverages, and shelter to hotel residents and firefighters.

The first missing firefighter found was Robert Jordan of Truck Company 2, who had died. When Mrs. Edyth Jordan came to the scene in search of her husband, clutching a newspaper photo of him at another fire, unknowing firefighters told her that he was injured. She went to Presbyterian Hospital believing him to be alive, but was informed that he had died from his injuries.

A few hours later, firefighters recovered the bodies George Malik and John Jarose, both of Engine Company 31.

One of the members who was trapped, Ray Nowicki, was stuck in a pocket of debris that was not yet reachable. Firefighters talked to him while they worked to find a way to rescue him. “I’m fine just take it easy,” he said to the crew. In the meantime, firefighters held Dr. Joseph Campbell down into the hole by the ankles so he could administer a pain-killing shot to Nowicki. Dr. Herman Bundesen crawled into the pile to give a shot of morphine to Firefighter John Measner while firefighters passed bricks hand-to-hand to remove Measner from the wreckage.

Lieutenant Theodore Patronski wondered if he and nine of his colleagues would ever be found: “…we heard people working overhead. We shouted for a long time. They never seemed to hear us.” They were trapped in a ten-foot square hole. Rescuers found them when they spotted Patronski’s leg in the debris.

The search continued for Captain Nicholas Schmidt of Engine Company 107 and Firefighter Robert Schaack of Truck 19. Lillian Schmidt and her two daughters stood vigil at home with rosaries in hand, praying for the safe return of their firefighter. The Schmidt’s two sons waited for word of their father at the scene. But a crane was brought to the scene to help firefighters clear the debris—and the bodies Captain Schmidt and Firefighter Robert Schaack were later found.

Thanks Drew

Tags: Chicago FD Captain Nicholas Schmidt, Chicago FD Lieutenant Theodore Patronski, Chicago Fire Department history, Chicago Firefighter George Malik, Chicago Firefighter John Jarose, Chicago Firefighter John Measner, Chicago Firefighter Robert Jordan, Chicago Firefighter Robert Schaack, chicagoareafire.com, Fatal fire in Chicago 12-17-53, Reliance Hotel Fire in Chicago

May 4

Posted by Admin in Fire Department History, Historic fire apparatus | 6 Comments

Peter Pirsch with the smoke ejector in 1931. Kenosha History Center

Excerpts from kenoshanews.com:

It would be impossible to count the number of lives saved by the use of fire engines and equipment manufactured over the years by Kenosha’s Peter Pirsch & Sons, but 92 years ago last month, Kenosha native Peter Pirsch, his employees, and a prototype from his factory were directly responsible for saving the lives of 16 men, all in one stroke.

The telephone rang in the home of Peter Pirsch at midnight on April 13, 1931. Chicago Fire Department Commissioner Michael J. Corrigan urgently needed his help.

Corrigan said that at the intersection of 22nd and Laflin Streets in Chicago, 35 feet below the surface, sewer workers of the Chicago Sanitary District were working construction on a 450 ft. sewer tunnel.

Earlier in the evening about 6:30 pm, workers were using a candle to determine the location of a leak in the tunnel when a pile of sawdust ignited. The men tried extinguishing the fire unsuccessfully for about 45 minutes before turning in a fire alarm. The first apparatus on the scene was Truck 14 and with Captain Timothy O’Neil. A thin curl of smoke was all that could be seen from the surface.

O’Neil and four firemen without breathing equipment rushed into the elevator and were lowered down to the tunnel. Three came back up 15 minutes later, with severe smoke inhalation. The smoke and gases were overpowering.Next, men from Engine 23 went down without masks and tanks with the same result. Firefighters from the suburbs, which had better equipment, arrived with masks and tanks. They lent them to Chicago firefighters, who kept trying to rescue the growing number of people inside.

This sequence of events was repeated again and again as no one at the surface had an accurate understanding of the intensity of the fire, smoke, and gases inside the tunnel.

After hours of attempts, the construction company informed the fire chief that some of the men — missing sewer workers and firefighters — could have sealed themselves at the far end of the tunnel inside an airtight compartment.

Back on the phone to Kenosha, Corrigan wanted Pirsch to bring a new smoke ejector unit that Pirsch had in his factory. If Pirsch could bring the machine, they could pump out the smoke and fumes and the men below the surface might be saved.

The smoke ejector, basically a huge air blower, was the invention of Minneapolis Fire Chief Charles Ringer. Manufacturing rights, however, were owned by Peter Pirsch & Sons.

At that moment, a smoke ejector was sitting in the Pirsch factory. Pirsch made phone calls and had a dozen of his men meet him at the plant.

The invention prototype was in its second stage: the model had been perfected and dismantled and the second machine was in the process of being connected to the chassis. In a matter of hours the task was completed.

Pirsch, and employees Ed Wade and George Williams left in the wee hours of the morning for Chicago, enlisting the aid of a rookie Kenosha policeman to drive the vehicle.

Years later, Pirsch would swear to the story that they made the 60-mile trip in 88 minutes — with an untested chassis. A pretty quick trip for 1931 era roads and vehicles.

A police car stopped them at the Chicago city limits, but instead of offering to escort them, the officers threatened to throw them in the slammer for speeding! The officers knew nothing of the fire.

Pirsch told them to lead his party to Laflin Street and 22nd … if a legion from the Chicago Fire Department wasn’t there, they could throw him in jail.

It was sheer bedlam as the truck approached the scene at daybreak. Seven hundred fireman and thousands of people filled the streets.

More than 50 firefighters who had entered and exited the tunnel were suffering from smoke inhalation. Some bodies had been recovered. By then, the state mine superintendent from Springfield had suggested sealing up the tunnel to extinguish the fire; a move that meant certain doom for the trapped men.

Pirsch, Wade, and Williams donned gas masks to set-up the blower and the truck was backed up to the shaft where two long tubes were lowered deep into the abyss. Then the blower was revved-up and engaged.

The suction drew the smoke and gas fumes out with one tube at a rate of 20,000 cubic feet of smoke per minute, while the other carried fresh air in.

Down in the tunnel, the men in the sealed chamber had been able to get some air from a pipe that extended to the surface, but that supply wasn’t nearly enough to sustain them. One of the 17 had succumbed to the smoke, and the others knew they had to make a break for the shaft very soon or suffer the same fate.Back on the street, Pirsch checked his watch: 23 minutes had passed. Suddenly, a patrolman let out a whoop! There in the smoke, first one form then another, until 16 men, some on their knees, all coughing and bleary-eyed, emerged from the shaft.

The crowd went wild and the families of the men who had been trapped rushed to help them.

Then it was time to bring out the dead. Seven sewer workers and four firefighters. Injured were 54 firefighters and laborers.

The Illinois Fire Service Institute reported the four men who died in the line of duty were Capt. Timothy O’Neil from Truck 14, one of the first to enter the tunnel; Firefighter Edward Bryon Pratt of Squad 8; and Firefighters William Coyne and William Karstens of Engine 23.

Pirsch and his smoke ejector made the headlines in newspapers around the world as he and his men were given credit for saving the 16 lives.

Peter Pirsch died on July 14, 1954 at the age of 88.

thanks Dennis

Tags: Chicago FD Captain Timothy O’Neil, Chicago Fire Department Commissioner Michael J. Corrigan, Chicago Fire Department history, Chicago Firefighter Edward Bryon Pratt, Chicago Firefighter William Coyne, Chicago Firefighter William Karstens, chicagoareafire.com, Ed Wade, George Williams, Minneapolis Fire Chief Charles Ringer, Peter Pirsch & Sons, Pirsch smoke ejector

This from Steve Redick:

I want to share something amazing for my fellow Chicago FD fans. This is a recording of operations in the Main Fire Alarm office in 1957 during a 3-11 fire. It came from the archives of my friend, mentor, and boss Jim Evans. The mic was open allowing us to hear telegraph signals, radio transmissions, and various phone conversations of the operators. This is an amazing piece of history … companies long out of service, fire insurance patrols, early radio operations … just amazing things. Listening to the telegraph signals alone is incredible if have the knowledge to interpret them as many of us older fellas have. I don’t know if Jimmy actually recorded this or acquired it somehow. It is a onetime opportunity to listen to history. Most, if not all of the operators heard in this recording are gone. I recognize a few voices.

Tags: audio recording from the Chicago FD Main Fire Alarm office in 1957 during a 3-11 fire, Chicago Fire Department history, chicagoareafire.com, historic audio from 3-11 Alarm fire in Chicago

Mar 3

Posted by Admin in Fire Department History, Historic Fire Photo | Comments off

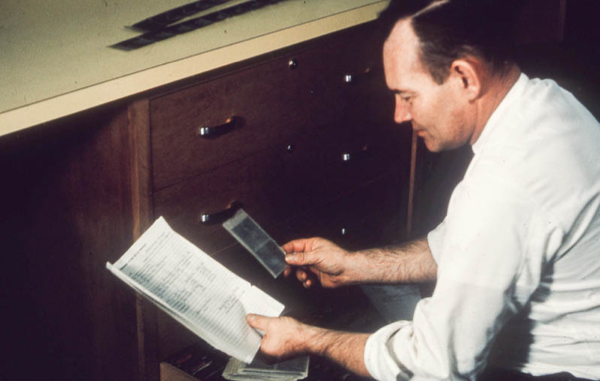

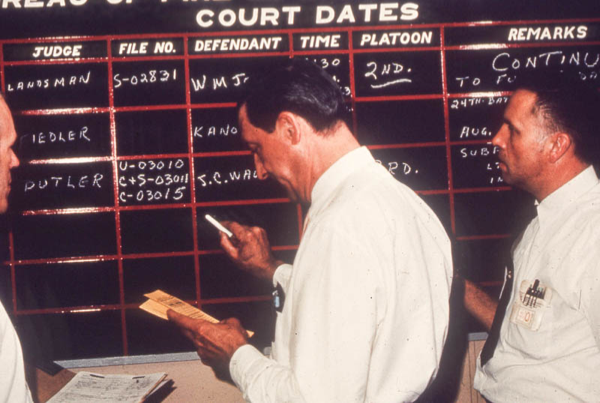

Vintage images assembled by Steve Redick depicting the Chicago FD Office of Fire Investigation

photographer unknown

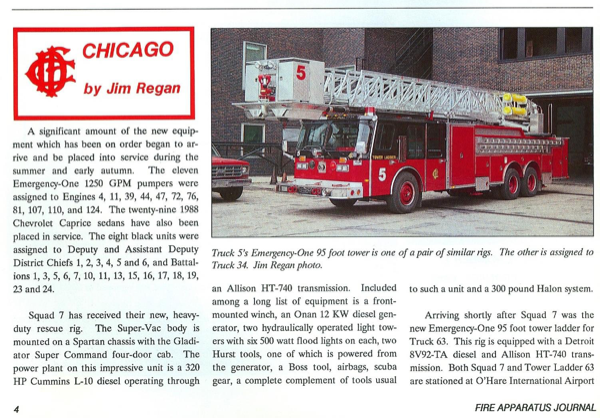

photographer unknown

photographer unknown

photographer unknown

photographer unknown

photographer unknown

photographer unknown

photographer unknown

photographer unknown

photographer unknown

photographer unknown

Tags: Chicago FD Office of Fire Investigation, Chicago Fire Department history, chicagoareafire.com, vintage Chicago FD photos

Mar 1

Posted by Admin in Fire Department History, Historic Fire Photo | Comments off

This from Steve Redick:

5-11 3620 S. Iron Street 6-8-64

photographer unknown

Tags: 5-11 Alarm fire in Chicago 6-8-64, Chicago Fire Department history, chicagoareafire.com, historic 5-11 Alarm fire in Chicago 6-8-64, massive fire in Chicago

Feb 28

Posted by Admin in Fire Department History, Historic Fire Photo | 3 Comments

Vintage images assembled by Steve Redick depicting the Chicago FD photographers

photographer unknown

photographer unknown

photographer unknown

photographer unknown

photographer unknown

Tags: Chicago FD photo unit, Chicago FD photographers, Chicago Fire Department history, chicagoareafire.com, historic Chicago FD photos

For the finest department portraits and composites contact Tim Olk or Larry Shapiro.

Arclite theme by digitalnature | powered by WordPress